PUTTING IT IN PERSPECTIVE

(Adapted from a presentation by Dennis Connors, history curator, Onondaga Historical Association)

History can give us perspective.

When considering the future of the I-81 viaduct, it’s instructive to look back at past transportation corridor decisions that had major and longlasting impact on the area.

When the Erie Canal became obsolete in 1918, the city had to decide what to do with it. Little thought was given to the canal’s potential as an aesthetic feature for the city; assuming maintenance of the locks was not of interest to the city and the often malfunctioning bridges that spanned the canal impeded movement throughout the city. The canal was seen as a transportation corridor holding the city back in the booming 1920s – to get rid of it was not a controversial decision.

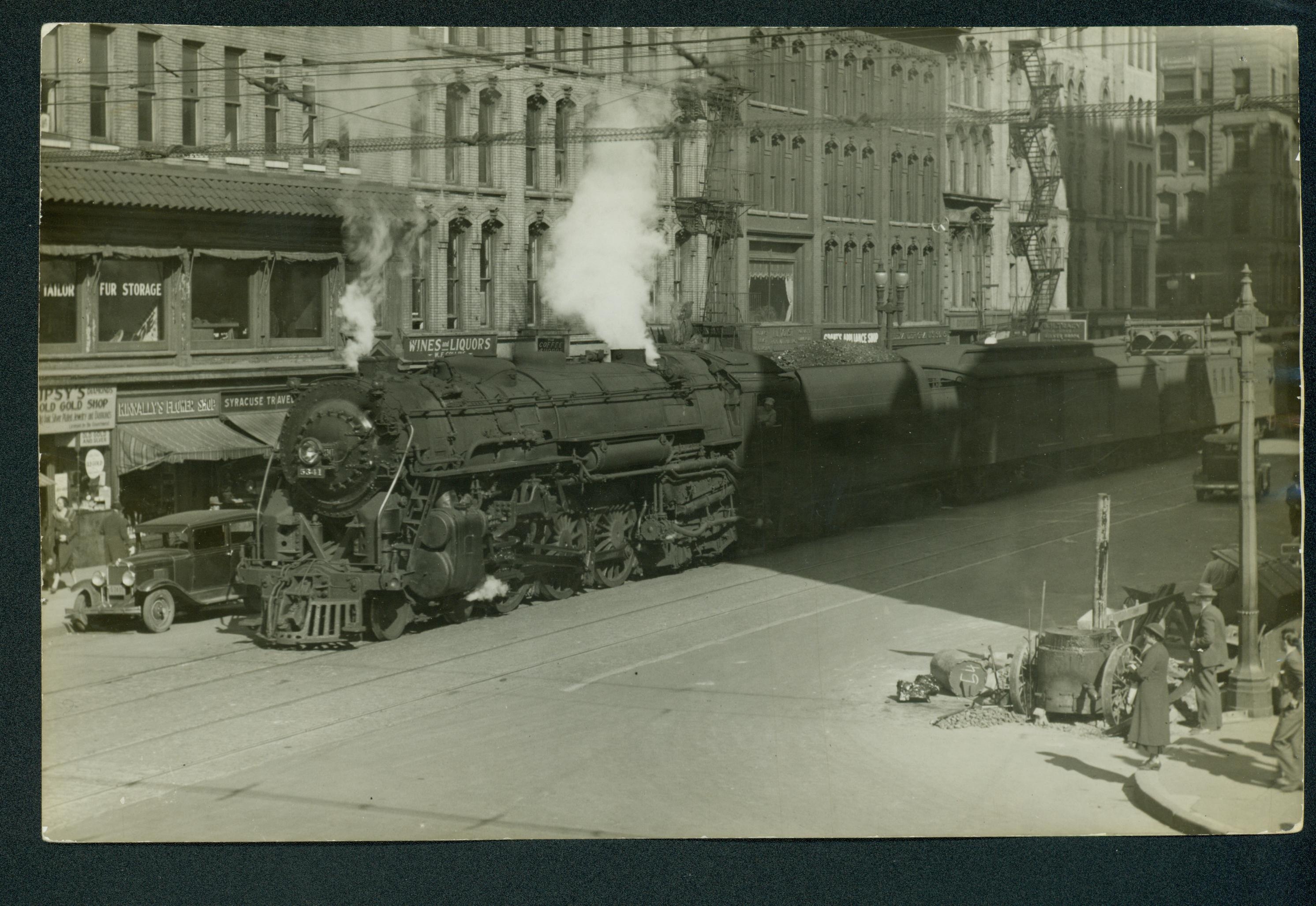

The Washington Street railroad corridor, however, was an even greater divider of the city, but because its station was used by more people than the canal, decisions related to its fate were far more divisive. By the turn of the last century, every single passenger train on the New York Central ran down Washington Street and all the DL&W trains ran through the Westside, many of those freight trains hauling coal. AT STREET LEVEL! No safety measures such as flashing lights or arms existed, causing numerous vehicle and pedestrian accidents. Opening a window in a nearby building at the wrong time meant a face full of soot and smoke.How did the rail lines get there in the first place? In 1837 when the little village of Syracuse granted the perpetual easements to the Syracuse and Utica Railroad for a little set of rails, for trains that barely reached 20 MPH speeds, Washington Street was only developed for a couple of blocks before it ran out into the country. And it was convenient to the canal packet boat lands a block away so people could make their intermodal connections.

Eventually, S&U RR became part of NY Central and technology and lifestyle changes made the decision a major problem by 1907.Any solution to the growing problem had to involve the agreement of the privately-owned railroads. Ultimately, two plans were advanced and went to public referendum. 1) Reroute the railroad far to the north. 2) Elevate the track just north of the Erie Canal, on a secondary right-of-way owned by New York Central. In an era when passenger railroad travel was a main mode of transportation, and downtown was clearly the hub of the city, the population couldn’t envision their major transportation center located away from the downtown. Also, the railroad interests wanted to remain downtown.

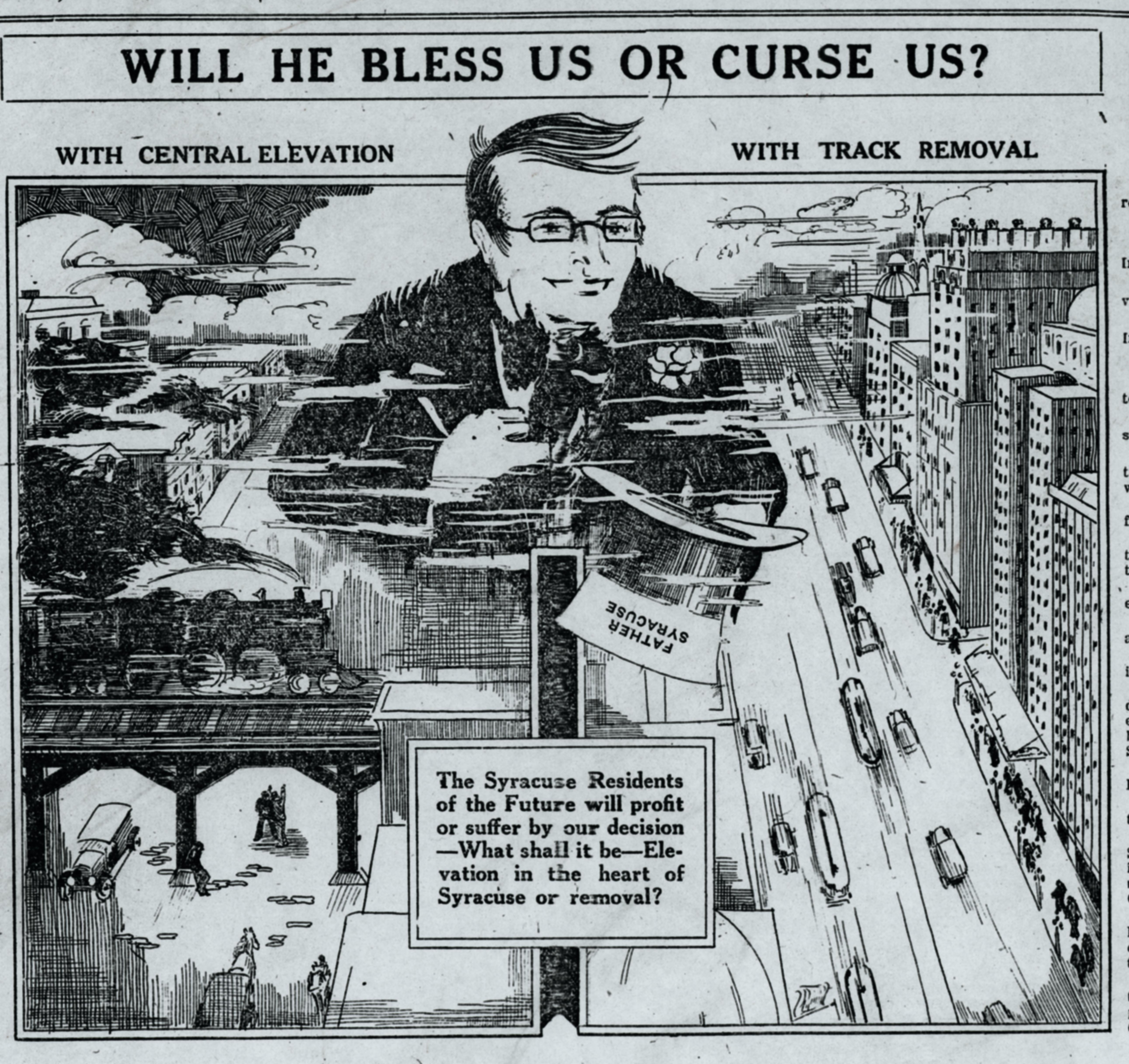

In the ensuing public debate, some people envisioned a growing downtown, others a lessening role. People saw the elevated tracks in different aesthetic lights. The promise that the railroad elevations could be made attractive and the sense that the railroad interests wouldn’t cooperate if the public voted to relocate passenger lines outside downtown, led citizenry to vote the second, more expedient solution of elevating track. However, it was a very public debate with the issue of the aesthetics playing a major role.  (Newspaper cartoon from the 1920’s courtesy Onondaga Historical Association).

(Newspaper cartoon from the 1920’s courtesy Onondaga Historical Association).

What the public couldn’t foresee was how the railroad would almost immediately begin to lose ground and how radically the transportation landscape would soon be altered. By 1962, when passenger traffic had nose-dived, NY Central moved the passenger lines to the Northern route, the original rerouting plan for trains, and the route that is still used today. And the old elevated railroad tracks became the route of the East-West Highway, I-690.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when the route for an elevated Rt. 81 was being planned, the negative aesthetics were again raised by some, but the decision was not subject to a public referendum.

These historical precedents show us that there are several factors that should be considered by a community when it is planning transportation corridors, in addition to simply cost and the fastest movement of traffic. The design and location of transportation corridors can have long-lasting impacts on quality of life issues and adjacent land use economics.