Post #4

CREATING AN URBAN MOBILITY PLAN

The issue of the redesign of the Route 81-Almond Street corridor is especially important because of its potential to strengthen the connection between downtown and the University Hill area, where the educational and medical institutions are expanding and planning further growth. These institutions will not only transform the Hill, they have the potential to transform downtown, and with downtown, form the thriving nucleus of a newly robust regional economy.

When the Onondaga Citizens League opted to “rethink I-81” as its study topic, it based the decision in part on the importance of improving the visual and physical connection between downtown and the Hill, as well as the knowledge that the deteriorating I-81 bridges will have to be rebuilt, not just repaired, in a few years.

Another critical factor in the decision to study the impacts of I-81 alternatives was the preliminary conclusion of a nationally recognized engineering and design firm, a finding that made it possible to think realistically about the possibility of removing interstate traffic from the middle of the city.

Growth in the Hill area had prompted a study of transportation needs of the area bounded by I-81, I-690, Thornden Park, and the southern boundary of the SUNY ESF campus. Recognizing that traffic congestion and parking problems on the Hill required more than just a study of vehicle use and parking space, the Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council (SMTC) undertook a comprehensive University Hill Transportation Study. The SMTC study findings form an important blueprint for growth in the coming decades.

Completed in 2007, in partnership with the engineering and design firm Edwards and Kelcey, the Hill Study includes land use projections based on the planned visions of the major institutions and property owners in the area, an analysis of the needs of pedestrians and bicyclists, an overall mobility needs assessment, examination of a variety of case studies, and the beginning of a brainstorming process that outlines some forward-thinking possibilities for consideration, including an integrated transit network, parking strategy, and bicycle boulevard network, as well as a mixed use development plan to create a walkable, vibrant neighborhood.

Completed in 2007, in partnership with the engineering and design firm Edwards and Kelcey, the Hill Study includes land use projections based on the planned visions of the major institutions and property owners in the area, an analysis of the needs of pedestrians and bicyclists, an overall mobility needs assessment, examination of a variety of case studies, and the beginning of a brainstorming process that outlines some forward-thinking possibilities for consideration, including an integrated transit network, parking strategy, and bicycle boulevard network, as well as a mixed use development plan to create a walkable, vibrant neighborhood.

Among the Emerging Concepts presented by the consultants was an analysis that showed that removal of the I-81 viaduct might be feasible with an enhanced surface-level Almond Street – Urban Boulevard and relocation of the I-81 through traffic to I-481, with corresponding improvements to the merges of those routes. While a boulevard in place of the I-81 viaduct is a long-term project requiring extensive study, among the Final Recommendations of the Hill Transportation Study report is reconfiguration of the Almond Street corridor, including fewer lanes, modern roundabouts, and streetscape improvements in order to improve pedestrian and bicyclist safety, improve traffic operations and increase the incentive to walk between downtown and the Hill.

The transportation study is based on the assumption that a comprehensive strategy has to focus on the movement of goods and people – not just cars – and that good land-use planning can alleviate traffic congestion, reduce the need for parking, and support transit, biking and walking. Even apart from the I-81 issue, SMTC’s University Hill Transportation study and its recommendations represent an exhilarating departure from the traditional approach to problem-solving. It offers the Syracuse metropolitan area a way to incorporate the community’s goals for quality of life, economic viability and environmental sustainability into the transportation planning process.

The transportation study is based on the assumption that a comprehensive strategy has to focus on the movement of goods and people – not just cars – and that good land-use planning can alleviate traffic congestion, reduce the need for parking, and support transit, biking and walking. Even apart from the I-81 issue, SMTC’s University Hill Transportation study and its recommendations represent an exhilarating departure from the traditional approach to problem-solving. It offers the Syracuse metropolitan area a way to incorporate the community’s goals for quality of life, economic viability and environmental sustainability into the transportation planning process.

Very soon, SMTC will launch a public participation project on behalf of the NYS Department of Transportation on the history, role, functions, and condition of I-81, to create awareness of DOT’s I-81 Corridor Study and to gather public input on issues and concerns related to I-81 and its environs. Ultimately SMTC, and DOT, hope to engage the community in the decision-making process related to future of I-81. OCL’s “Rethinking I-81” study and this weblog are meant to inform and contribute to that process.

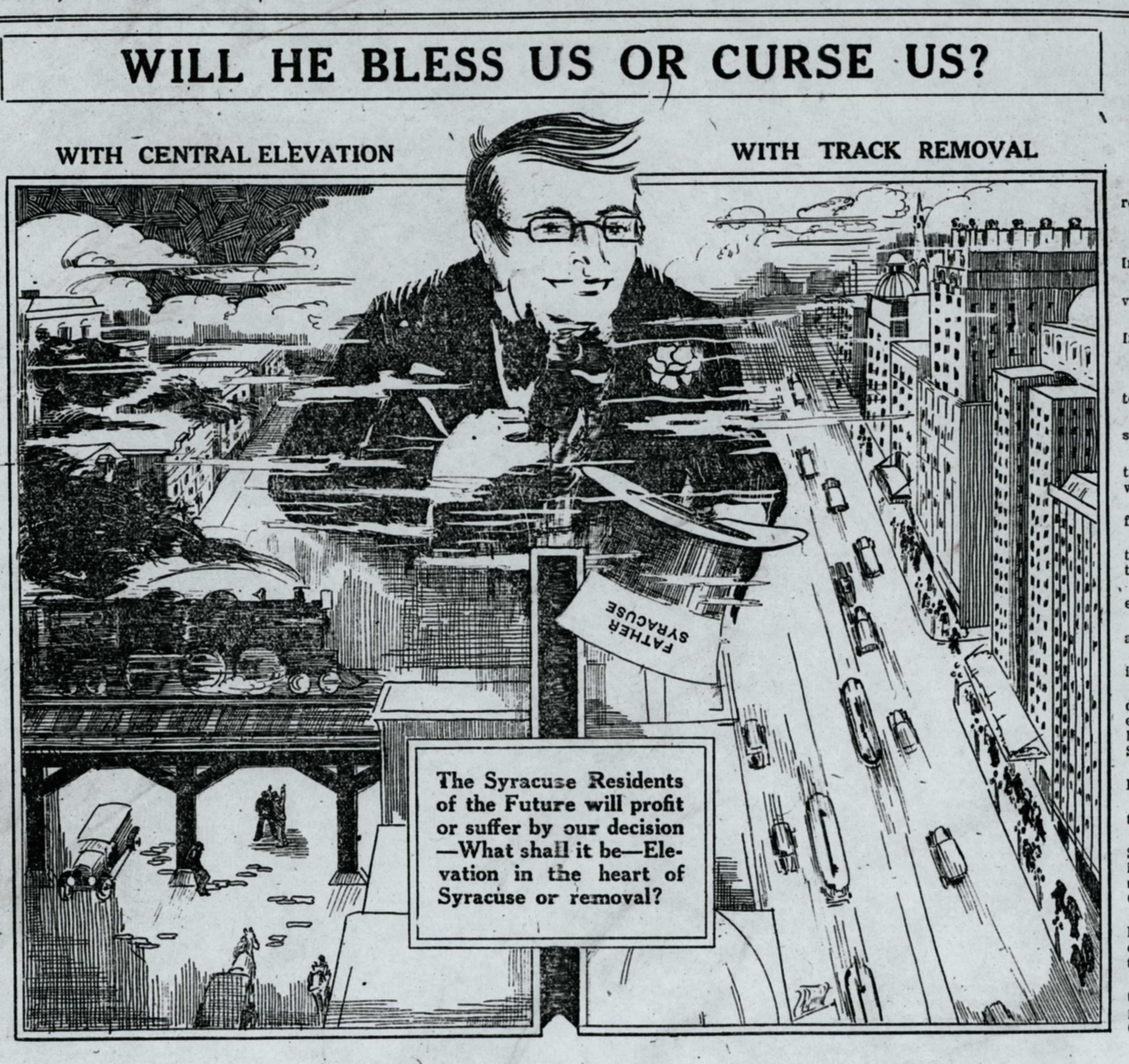

(Newspaper cartoon from the 1920’s courtesy Onondaga Historical Association).

(Newspaper cartoon from the 1920’s courtesy Onondaga Historical Association).