WHAT WOULD HAPPEN IF I-81 DOWNTOWN CLOSED?

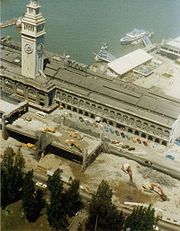

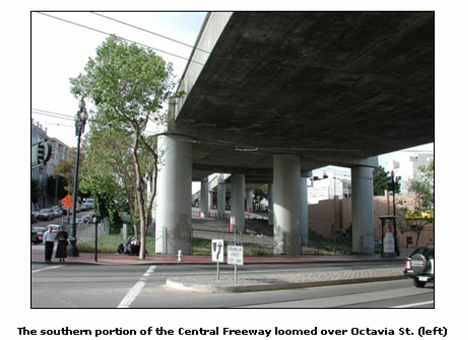

When we think about engineering solutions to traffic problems, it’s useful to keep in mind that human behavior is a key variable in the equation. Drivers adjust their behavior to the situations presented to them. When the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake damaged San Francisco’s Central Freeway, the destroyed northern portion of the viaduct was demolished, while the southern portion, running above Octavia Street, remained. A city task force recommended replacing the elevated freeway with a surface boulevard that would make it easier for local traffic to access the neighborhood, but the state department of transportation decided to rebuild the deck. When the reconstruction project began, the predicted gridlock failed to materialize; local streets handled the traffic without any major problems. With this evidence that the street grid could handle most of the traffic when the freeway was shut down, neighborhood residents ultimately were able to force a referendum that ended in removal of most of the freeway and the creation of Octavia Boulevard.

What would happen if sections of Interstate 81 through Syracuse were shut down for an extended period? We actually have some experiences that give us an indication of how Central New Yorkers would react to a planned closure of a main route to downtown and the University Hill area. Ten years ago, construction closed the northbound lanes of I-81 from the Brighton Avenue exit to the Harrison Street on-ramp for about three months. When that project was complete, the southbound lanes were closed from Interstate 690 to Calthrop Avenue. It was the first major closure since I-81 north was shut down for eight months in 1988 to repair badly deteriorated bridge decks.

For months before the shutdown, the State Department of Transportation conducted a massive campaign to inform city officials, businesses, and residents about the project and alternative routes. The newspapers were full of warnings for weeks in advance of the construction for the estimated 30,000 drivers a day who took I-81 north through Syracuse. In addition, plans including street sign and traffic signal changes, additional traffic police, and even a free OnTrack train between Jamesville and Armory Square were put in place to keep traffic moving.

“Where’s the Rush? First Day of I-81 Detour Goes Smoothly” was the headline on the May 27, 1999 Post-Standard story. At the peak of the first rush hour affected by the northbound shutdown, “…there was virtually no traffic on the detour route where state transportation officials feared a major backup.” Commuters found their own quickest secondary routes to use, diverting cars from the detour routes and allowing traffic to flow smoothly.

Commuters leaving downtown during the afternoon rush hour had a more difficult time after DOT shut down the I-81 connector to I-690, and the Harrison Street on-ramp was reduced to one lane. As drivers avoided the on-ramp and learned to use alternate routes to access I-690 east, traffic eased over the following days, though backups at intersections still occurred, as drivers, particularly those heading north, headed to the Harrison Street ramp. Deck repairs north of downtown closed lanes and slowed traffic in that area, but even those slowdowns added less than five minutes to total commute time, the DOT spokesman was quoted as saying.

The OnTrack commuter train, which offered free rides between Jamesville and Armory Square during the construction, averaged only 35 riders a day, because, it was assumed, the gridlock that was expected to cause severe traffic delays never occurred. “Motorists and police feared gridlock would seize the city when a 2 ½ mile stretch of I-81 northbound lanes were closed in May for repairs. But the back-ups were minor.” (The Post-Standard, August 19, 1999 pg. A1).

When DOT closed down I-81 south, including the connectors from I-690 east and west, affecting nearly 35,000 daily travelers, DOT officials were more optimistic. In fact, the closure of I-81 south to replace expansion joints and make other repairs, generated almost no news, and apparently only minor traffic tie-ups. Commuters seemingly adjusted their schedules or their routes through the 2 ½ months of repairs. As then assistant DOT regional director George Angeloro said during the northbound shutdown: “Traffic is like water. It seeks its own levels.”

A temporary shutdown can give us a partial indication of what might happen if the highway were replaced with an alternative roadway. As in other cities that have permanently eliminated a freeway, improvements to the surrounding street grid, as well as pedestrian, bicycle, and transit considerations, would be part of the mobility plan.